Square and Circle

February 10, 2025

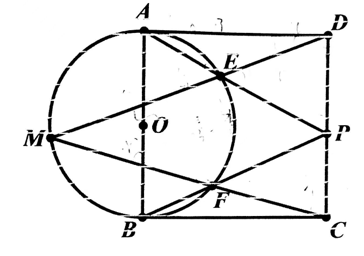

Given a square ABCD, draw a circle O with AB as diameter. Pick a point P on side CD. Line AP intersects circle O at point E. Line BP intersects circle O at point F. Line DE and CF intersect at point M. Show that M is also on circle O.

Let \(\alpha = \angle PAD\), \(\beta = \angle PBC\). Let the radius of circle \(O\) be 1, then \(AE = 2\sin\alpha\). Let \(x = \angle ADM\), \(y = \angle BCM\), then \(\angle AEM = \alpha +x\), \(\angle BFM = \beta +y\).

Our goal is to show that \(x + \alpha + y + \beta = 90^\circ\).

By the Law of Sines, we have \[\begin{align} & \frac{AE}{AD} = \frac{\sin x } { \sin (\alpha + x)} = \sin \alpha \\ \implies & \sin x = \sin(x+\alpha - \alpha) = \sin (\alpha + x ) \sin \alpha \\ \implies & \sin(x+\alpha) \cos\alpha - \cos(x+\alpha)\sin\alpha = \sin (\alpha + x ) \sin \alpha \\ \implies & \tan \alpha = \frac{\sin(x+\alpha)}{ \sin (x + \alpha) + \cos(x+\alpha)} \end{align}\] Similarly, we have \[\begin{align} \tan \beta = \frac{\sin(y+\beta)}{ \sin (y + \beta ) + \cos(y+\beta)} \end{align}\] Note that \(\tan \alpha + \tan \beta =1\), hence \[\begin{align} \frac{\sin(y+\beta)}{ \sin (y + \beta ) + \cos(y+\beta)} = \frac{\cos(x+\alpha)}{ \sin (x + \alpha) + \cos(x+\alpha)} \end{align}\] which can be simplified to \(\cos (x + \alpha + y + \beta) = 0\), i.e. \(x + \alpha + y + \beta = 90^\circ\). Connect BE, we have \(\angle BEM = \angle BFM\), which implies that \(M\) is on the circle.

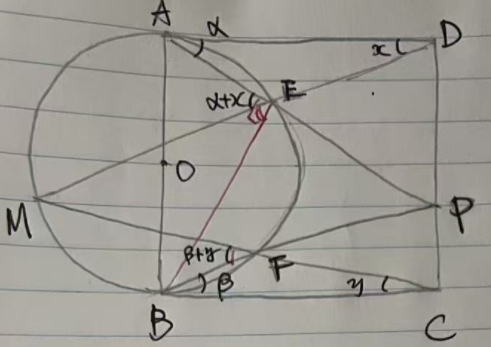

Let \(\alpha = \angle PAD\), \(\beta = \angle PBC\), \(a = \tan \alpha\), \(b = \tan \beta\), then we have \(a+b=1\). Let \(k = ab\), note that \(0 < k \le \frac{1}{4}\) and \(a^3 + b^3 = (a+b)^3 - 3ab(a+b) = 1 - 3k\). Let the radius of circle \(O\) be 1, then \(AE = 2\sin\alpha, AP = 2\sec \alpha\).

Let \(x = \angle ADM\), \(y = \angle BCM\), \(DM\) intersects \(AB\) at point \(X\), \(CM\) intersects \(AB\) at point \(Y\). Then \(AX = 2\tan x\), \(BY = 2\tan y\), \(XY = 2 ( 1- \tan x - \tan y)\). Note that \[\begin{align} \frac{AX}{DP} = \frac{AE} {EP} \implies \frac{\tan x} {\tan \alpha} = \frac{\sin\alpha} {\sec \alpha - \sin \alpha} \\ \implies \tan x = \frac{1-\cos 2\alpha} {2 - \sin2\alpha} = \frac{a^2}{a^2 - a + 1} = \frac{a^2}{a^2 + b} \end{align}\] Similarly, we have \[ \tan y = \frac{1-\cos 2\beta} {2 - \sin2\beta} = \frac{b^2}{b^2 - b + 1} = \frac{b^2}{b^2 + a}. \] Note that \[\begin{align} %\tan x \cdot \tan y & = \frac{a^2}{a^2 + b} \cdot \frac{b^2}{b^2 + a} = \frac{(ab)^2}{a^3 +b^3 + (ab)^2 + ab} = \frac{(ab)^2}{(ab)^2 - 2ab + 1} = \frac{k^2}{(1-k)^2}\\ \tan x \cdot \tan y & = \frac{a^2}{a^2 + b} \cdot \frac{b^2}{b^2 + a} = \frac{(ab)^2}{a^3 +b^3 + (ab)^2 + ab} = \frac{k^2}{(1-k)^2}\\ %\tan x + \tan y & = \frac{a^2}{a^2 + b} + \frac{b^2}{b^2 + a} = \frac{a^3 + b^3 + 2(ab)^2}{(1-ab)^2} = \frac{2k^2 - 3k +1}{(1-k)^2} = \frac{1-2k}{1-k}. \tan x + \tan y & = \frac{a^2}{a^2 + b} + \frac{b^2}{b^2 + a} = \frac{2k^2 - 3k +1}{(1-k)^2} = \frac{1-2k}{1-k}. \end{align}\] From \(M\) draw height \(MQ \perp AB\). Our goal is to show that \(MQ^2 = AQ \cdot BQ\).

Let \(h = MQ\). Note that \[\begin{align} \frac{MQ}{MQ+2} = \frac{XY} {DC} \implies \frac{h} {h+2} = 1 - (\tan x + \tan y) \\ \implies h = 2(\frac{1}{\tan x + \tan y}-1) = \frac{2k}{1-2k}. \end{align}\] We also have \(AQ = (h+2) \tan x\), \(BQ = (h+2) \tan y\), \[\begin{align} AQ \cdot BQ = (h+2)^2 \cdot \tan x \cdot \tan y = \frac{(2-2k)^2}{(1-2k)^2} \cdot \frac{k^2}{(1-k)^2} = MQ^2 \end{align}\] Hence \(\angle AMB\) is a right angle which implies \(M\) is on circle \(O\).

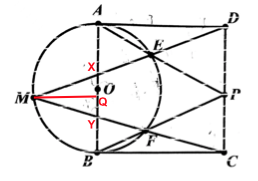

Let the radius of circle \(O\) be 1. Let \(DP = 2a\), \(CP = 2b\), then \(a+b = 1\). \(DM\) intersects \(AB\) at point \(X\), \(CM\) intersects \(AB\) at point \(Y\). \[\begin{align} \frac{AE}{AB} = \frac{DP} {AP} \implies \frac{AE} {AD} = \frac{DP} {AP} \\ \frac{AX}{DP} = \frac{AE} {EP} \implies \frac{AX} {AD} = \frac{DP^2} {AP \cdot EP} \end{align}\] Similarly, we have \[\begin{align} \frac{BY}{BC} = \frac{CP^2} {BP \cdot FP} \end{align}\] By Power of a point, we have \[\begin{align} AP \cdot EP & = BP \cdot FP = (PO - 1)(PO+1) = PO^2 - 1 \\ & = 4(a^2 - a + 1) = 4(b^2 - b + 1) \\ & = 4(a^2+b) = 4(b^2+a) = 4 (1-ab) \end{align}\] Let \(AX = 2x, BY = 2y\), \(k=ab\), then we have \[\begin{align} x = \frac{AX} {AD} & = \frac{DP^2} {AP \cdot EP} = \frac{a^2}{a^2 - a + 1} = \frac{a^2}{a^2 + b} = \frac{a^2}{1-ab} \\ y = \frac{BY} {BC} & = \frac{CP^2} {BP \cdot FP} = \frac{b^2}{b^2 - b + 1} = \frac{b^2}{b^2 + a} = \frac{b^2}{1-ab} \\ x \cdot y & = \frac{a^2}{a^2 + b} \cdot \frac{b^2}{b^2 + a} = \frac{k^2}{(1-k)^2}\\ x + y & = \frac{a^2}{a^2 + b} + \frac{b^2}{b^2 + a} = \frac{2k^2 - 3k +1}{(1-k)^2} = \frac{1-2k}{1-k}. \end{align}\]

From \(M\) draw height \(MQ \perp AB\). Our goal is to show that \(MQ^2 = AQ \cdot BQ\). Let \(h = MQ\). Note that \[\begin{align} \frac{MQ}{MQ+2} = \frac{XY} {DC} \implies \frac{h} {h+2} = 1 - ( x + y) \\ \implies h = 2(\frac{1}{x + y}-1) = \frac{2k}{1-2k}. \end{align}\] We also have \(AQ = (h+2) x\), \(BQ = (h+2) y\), \[\begin{align} AQ \cdot BQ = (h+2)^2 \cdot x \cdot y = \frac{(2-2k)^2}{(1-2k)^2} \cdot \frac{k^2}{(1-k)^2} = MQ^2 \end{align}\] Hence \(\angle AMB\) is a right angle which implies \(M\) is on circle \(O\).

Let the radius of circle \(O\) be 1. Let the center of square be the origin \((0,0)\). Then \(C,D,P\) on the line \(x=1\). The equation of circle \(O\) is \((x+1)^2+y^2 = 1\).

Let \(P\) be \((1,t)\). The slope of \(DE\) and slope of \(CF\) can be solved as \(\frac{(t-1)^2}{t^2+3}\) and \(\frac{-(t+1)^2}{t^2+3}\) respectively. It turns out that coordinates of intersection point \(M\) can be solved as \[M = (-\frac{2}{t^2+1}, \frac{2t}{t^2+1}).\] One can verify that \(M\) indeed satisfies \((x+1)^2+y^2 = 1\).

Note that the mapping from \(P\) to \(M\) is actually the inversion from the line \(Re(z) = 1\) to the circle \(|z+1|=1\) by \(f(z) = -\dfrac{2}{z}\)..

Given a quadrilateral \(ABCD\) where \(C\) and \(D\) on the line \(Re(z)=1\), \(A\) and \(B\) on the circle \(|z+1|=1\) where \(A=f(D)\), \(B=f(C)\) and \(f(z) = -\dfrac{2}{z}\) Then the intersection of two diagonals \(AC\) and \(BD\) is also on the circle \(|z+1|=1\).

(Note that here \(f(z)\) can be a general Mobius transform that maps every line to a circle, and maps every circle to a line.)

The proof is left to the reader.

Let \(O\) be the origin. Let \(P\) be the intersection of the circumcircle of \(\triangle CDO\) and the circumcircle of \(\triangle ABO\).

Coming back to the original problem. Let the radius of circle be \(1\). Let the center of square be the origin \((0,0)\). Then \(C,D,P\) on the line \(Re(z)=1\) and the equation of circle \(O\) is \(|z+1| = 1\).

Let \(Q=f(P)\) where \(f(z) = -\dfrac{2}{z}\), then \(Q\) is on the circle \(|z+1|=1\). By Lemma 1, we know that \(QD\) and \(AP\) intersect the circle \(O\) at same point \(E\) since \(Q=f(P)\) and \(A=f(D)\). Similarly \(QC\) and \(BP\) intersect the circle \(O\) at same point \(F\) since \(Q=f(P)\) and \(B=f(C)\).

Therefore \(DE\) and \(CF\) intersect at point \(Q\). Hence \(M\) and \(Q\) are same point, which implies \(M\) is on circle \(O\).

Note that this proof only requires \(A=f(D)\), \(B=f(C)\) so it holds even when \(ABCD\) do not form a square..

Hint: Pascal’s Theorem